We all are hit with the worst condition of this pandemic; people such as the frontline health workers, sanitation workers, police personnel, social workers, and many volunteers are fighting to the best of their abilities to combat this situation.

What we don’t see is that the prisoners are like any other marginalized communities insofar as they are forgotten by the mainstream society. But they are trying their best to cater to the needs of the society to combat this pandemic. For many, this group of people doesn’t exist in the society; they are lock-downed much before the lockdown and isolated.

Rising Warriors Against The Virus

“After face masks, Kerala prisoners to now make hand sanitizers”- Deccan herald, March 18, 2020

“Jail inmates in Karnataka make reusable masks”- The Hindu, March 29, 2020

“After Kerala Maharashtra Ropes In Prisoners To Make Face Masks To Tackle Shortage”- Mumbai Live, March 2020

“UP prison inmates make masks, listen to ‘jail radios’ amid coronavirus lockdown”- Hindustan Times

These are some of the newspaper headlines in the past month which grabbed the attention of the nation. As our country was struggling to combat this unprecedented situation we also had a shortage of face masks and other essential items. Some states like Kerala, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, and Maharashtra woke up to the situation and utilized their imprisoned potential.

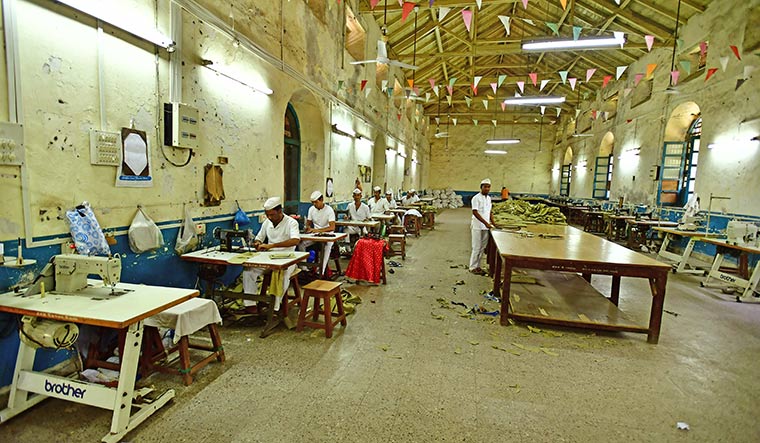

I have been working in Jamshedpur jail for the last couple of years, and during this pandemic, the prisoners made more than 36,000 masks to cater to the needs of the district. They have worked around the clock without any complaints when they could have slept like any other usual day. I was surprised to see their dedication to this job of making re-usable cloth face masks.

They are the same ostracized group from the larger society, and we haven’t bothered to remember them in our daily routine. Then, why are the prisoners catering to their needs? The simple answer I could gather is, their readiness to be a part of this fight comes from a sense of satisfaction of helping out. They want to feel that they too are a part of this society, and it’s an opportunity to prove it. But this group is still being ostracized from the larger society; we don’t speak about them nor do we want to.

In India, like many parts of the world, criminal are seen as someone to be excluded from the main society, that they do not belong here. We are forgetting the fact that not all people are criminals. There will be people with delinquent behaviours, but there are also people who had committed a crime as a momentary lapse, not intentionally.

I remember one of my early interactions with a top prison officer. He said, not all the people are criminals; those who make crime as a business never come to the prison. Taking a wrong step in life doesn’t mean they do not deserve a second chance to prove their better side. The momentary lapse or mistakes should not define one’s life forever. Sadly, the system never thinks much about mistakes, rather about the punishment.

Today 80% of the prisoners belong to the productive age (18-50 years; NCRB 2018), and we are not concerned about utilizing their potential. Many organizations give them training and knowledge, but not an opportunity to use that knowledge. It is important to have both vocational training and opportunities for prisoners within the jail.

Prisoners: The Current Reality

As per the National Crime Record Bureau data 2018, we have 1,339 (much less than 2016—1,412 prisons) prisons across India which hold a number of 4,66,084 prisoners against the capacity of 3,96,223. More than 70% of the prisoner’s population is under trial.

Youth population is also high in numbers. In India, 40% of the prisoners belong to 18–30 years, and 43% people belong to 30–50 years. In a human life, 18–50 years age-group is considered to be the productive age, but in prison, they are becoming unproductive.

Prison acts or prison manuals, followed by various committee report (Mulla Committee report as a major one), give guidelines to provide employment and education to the prisoners. The time-to-time update of prisoner manuals (latest in 2016) recommends employment or vocational activity as one of the major means of rehabilitation.

But sadly, states like Jharkhand haven’t adopted the Prison manual. West Bengal revised the 1894 prisoner act in 1957 and 67, Odisha in 2015 and Bihar in 2012. Many states haven’t gone through the updated prison manual, and the Model Prison Manual 2016 is in the draft state.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), United Nations Standard Minimum Rules of Treatment of Prisoners (Mandela Rules), the Doha Declaration by United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the prisoner manual, Prison Act—everything emphasizes on the importance of the right of the prisoners.

They also recommend creating a space for vocational training and opportunities for the prisoners to give them an option to earn income. It gives them new hope and a second chance to live in a peaceful environment after release, but we haven’t practically established it.

These lead to an increase in the number of repeat offences after release as they do not see any other option to move ahead in life. There are many committees established to understand the present condition of the prisoners in India, and all their recommendations are to create vocational opportunities for the prisoners.

It has been more than seven decades to our independence, but still, we haven’t had changes in the correctional setting. The world is moving faster; it speaks of restorative justice or reformation ideology to adapt to the correctional policies, and countries like New Zealand are doing a good job. But we are still practicing justice of retribution and stepping into rehabilitation. We have created rehabilitation centres and probation officers to manage a smooth rehabilitation process, but we haven’t succeeded in it.

Our system still believes in punishment as a means of preventing crime, from small theft cases to rape, murder or any other heinous crime. But even after seeing the increasing number of prisoners, we haven’t thought of a better alternative solution. There are some countries which have advanced in implementing alternative punishments, for example, community service for select offences. Creating more prisons and sending more people to jail is not the right way of preventing crimes; it will add to the burden of the state.

Hindrances In The Path!

Even if we want to work on rehabilitation and reformation of the prisoners by enhancing their abilities, there are many problems:

- Overcrowding becomes a challenging issue which has been prevailing for a long time. Prison occupancy rate comes around 120% at the national level, where in some of the states, it is more than 150%. An overcrowded jail may not be able to provide hygiene, proper bedding or sanitation facilities to prisoners, and they have to manage with limited resources. It will lead to various mental and health problems. Vocational engagement comes as a secondary priority for the prison management compared to accommodation of prisoners; therefore, lack of space is limiting the creation of various vocational training and opportunities.

- Infrastructure – Most of the prisons do not have proper recreational spaces or training facilities. Space is adjusted here. Prison is considered a place for punishment, and it curtails the rights of the people but doesn’t mean we shouldn’t give them a chance to improve within the prison. Therefore, creating spaces of learning and opportunities is important as well.

- Mental health is a challenging situation in the prison. There is no one to listen to, from management to fellow inmates, rather people judge. Recent studies show that most of the prisoners are suffering from depression, schizophrenia, stress, adjustment disorder, homesickness, etc., and most of the time, we fail to address these issues. People haven’t seen outside world, or their dear ones. There is no connectivity with their families, and it puts everyone in stress and depression. We should prepare them to accept the reality and to adapt to the situation. Until and unless we address the psychological needs of the prisoners, it is impossible to engage with them.

Excluded Among The Already Excluded

Women prisoners and the transgender community are even more forgotten in the entire discussion about the prisoners. The opportunities male prisoners get are not the same as for the female prisoners. Their world is even more limited with less connectivity.

When it comes to their vocational training and opportunities, we still think we should give them tailoring, pickle making, papad making, stitching, etc. as an option, coming from the same old-school thoughts influenced by patriarchal notions seeing women as weak. Their issues haven’t been spoken about much in the society; already they carry the burden of the social stigma, doubled than a male’s.

Society expects a woman to be much lenient, silent, surrendered to the superiority of the male; if they go beyond then, it is not expected behaviour. So, committing a crime by a woman is unimaginable and something that can’t be digested, even if she does it for her own protection.

In prisons, their opportunities are limited, and there is no space to grow or learn again. A second chance is always denied to the women prisoners. Their basic issues like personal hygiene are not given much priority, and they have to manage themselves. Their story hasn’t been heard by anyone, and mental torture they go through is unimaginable. A woman’s life ends within those walls.

The transgender community is not even mentioned in the entire NCRB data or any other policy. They have been not considered as part of the society.

Magical “Touch”

In the prison I work, I know Altaf (name changed). He was charged for murder and hasn’t seen the outside world for the past 13 years. But after a small touch of positivity in his life, he has become an artist and leads a group of artists in the Jail. Today, he writes a poem, paints and colours beautiful pictures to inspire many prisoners.

Working with a prisoner for the last few years taught me this: we can give them any training, but it is also important to provide a space to utilize those training to enable them to have a livelihood option within the prison.

As we have many projects to up-skill India, we should also focus to up-skill Indian prisons. It helps the prison authorities to create more avenues to engage prisoners, and prison management becomes easier and trouble-free to an extent. Through their earnings, it also becomes possible for them to support their family as well— they might be the only earning member in the family. Through vocational opportunities, we are also helping a family outside the prison as well and engaging the prisoner.

It is the right time to move ahead to restructure our penal system and correctional settings in the country. If we do not act now, then it is going to create a worse condition. It is time to reform the system, and bring a more humanitarian approach.

After all, prisoners are also human beings, and they deserve to be treated like a human. This is a time to remember the crisis and those who are fighting hard against this unprecedented situation. Prisoners did what they could do the best; they shouldn’t be forgotten after this battle. It is time to fight for their rights too.